Threading the needle

Just looking

हम तो बस देख रहे हैं…

It begins as all great shopping adventures do—with feigned casual indifference.

“There is a family-owned textile shop called Stuti Weaves in the textile district, and they have a tour. I read all about it in TOI (Times of India) We should go see it!” someone suggests.

The deceptive intention of this invitation is to simply observe; to admire the craft, the craftsmen, and hear the inspiring story of the woman who is single-handedly bringing back hand-loomed goods in Banaras.

The plan seems straightforward: visit the textile workshop, admire the skill of the artisans, and leave unburdened by new acquisitions.

But the hand looms speak, their steady rhythm echoing through the workshop.

The looms look as old as the land itself, and the cloth forming thread by thread seems impossibly beautiful for such antiquated technology to create—too delicate, too intricate—to be produced by such spindly rickety machines.

The weavers, hands moving in a blur with effortless precision, pull and thread, warp and weft, creating textures that are ancient and somehow always in style, cycling in and out of fashion dictated by the complex demands of the world beyond these walls.

Our group watches, first with vague curiosity, then, as the process is explained and the requirements of the artisan made clear, with admiration.

Someone leans in closer to inspect the gold zari threading; another murmurs about the mastery of the weave.

Some in IT remark on the similarity of the punch cards for the jacquard loom to the punch cards in the early days of business computing.

The quiet spell cast by suberb craftsmanship is setting in.

A Legacy Revived

It was Vandana Singh who first saw the struggles of Banaras’ weavers and the potential loss of a centuries-old craft.

Walking through the lanes of Varanasi, she noticed fewer and fewer artisans taking up the family tradition of weaving.

And so, Stuti Weaves was born—starting with just one loom, but carrying the weight of a revival movement.

But the business truly took flight when her daughter-in-law Anandana Singh and her husband left their corporate careers in 2019 to fully commit to the revival effort.

Together, they revived 200-year-old saree designs, supported over 300 weavers, and made Banarasi handloom textiles competitive in modern markets.

Their work was not just about selling sarees—it was about preserving a craft, sustaining livelihoods, and ensuring that the art of weaving remained a living tradition.

And now, with a subtlety not unlike some of the finest patterns on silk, the next movement of Khareedari ka Nach unfolds.

The classic dance of shopping

खरीदारी कथक का नाच

The innocent phrase “We are here anyway” holds a deceptive power in this early part of the dance, delivered in a way no less beguiling than the perfectly measured grace of the Kathak dancer, and if performed properly, a reward of praise and paise will materialize here as well. Let’s witness the delicate rhythm of the shopping dance. If you listen closely you can hear the beat of the ghungroo punctuating the end of each step. To experienced men, the inevitability is almost tangible as is the lightening of the purse. The transition from workshop to showroom is seamless, almost unspoken, meant to ease you gently out of the role of tourist and into the role of avid buyer. Stacks of fabric emerge one by one at the direction of the discerning eyes of the women shoppers, unfolding from a neat small rectangle to a flowing billowing saree unfurled in a dazzling display of color and texture.

The dance now begins in earnest. Men take their designated places—some standing directly behind, others strategically seated next to their partner, mentally preparing for the long haul ahead. The women, meanwhile, step into their element. Silks in shady greens, deep maroons, electric pinks, interwoven with gold and silver thread—each fabric touched, tested, assessed.

And then, the maneuver: feigned disinterest. A saree is held up, glanced at, then swiftly set aside with an air of studied neutrality. “No. Not quite right,” she says, though her fingers linger a second longer than necessary. The seller, experienced in this age-old dance, smiles knowingly. She does not push, does not insist. Instead, she patiently waits, confident in the inevitable return to the discarded piece, dutifully unfolding yet another.

The men observe this exchange with both amusement and helplessness. Some are dragged into the performance, expected to weigh in

“What do you think?”

Attention must be paid. Honest input must be given in a complete sentence with clear concise support for the opinion fully expected. A nod that is too eager might prolong the search; too passive, and there will be consequences later.

At this point, the full dance of the Khareedaree is fully underway.

The Conclusion: The Final Movement

Finally, one of the group has made a decision. They point to one of the sarees, now buried deep in a pile of colored, patterned silk—representing years of work by skilled weavers.

Lo, it is the one they knew they would buy all along. Yet still, they look at it with disinterest, as if it is their only choice among meager offerings—but alas, what else can be done?

The husband and wife had been chatting about the color, debating: Is it tastefully bright or loud and garish? Will it catch the right light? Will it suit the discerning eye of the one they will gift it to for an upcoming special engagement?

But still—the price must be settled.

I have witnessed a buyer wanting a lower price act convincingly annoyed at the “hiked prices and obvious gouging” of the seller.

And the seller, upon hearing their counteroffer, conjures actual tears!

He staggers as if stabbed in the heart—displaying his suffering with his quavering voice and every movement he makes.

For a brief moment, one can see his starving family, waiting in the wings of the performance.

And then, his final, lowest price is delivered—lest the buyer snatch more food from the mouths of his family, who are even now on the verge of death due to greedy customers unwilling to part with even one single paisa.

But not here—this is the most tasteful, up-market haggling I have ever seen.

The dukaandar (shop owner)—one of the designers herself—quietly writes the price on a piece of paper.

The subtle actions leading to the final choice—the hesitation, the quiet drama of their indecision—were enough to move the price down a little.

And the dukaandar says quietly, as if only to them, that due to the fact that they had spent time and paid to tour the shop, they would receive a 20% discount.

A price is quickly and quietly decided. Credit or UPI…

We all have our own version of this process, and finally, four shoppers emerge, grinning over our smart purchases.

We hold our bags in front of us like they are great prizes that we have been awarded. Someone snaps our picture, as if this is a momentous occasion. We are another sort of pilgrim today—where shopping for Banarasi silks was like visiting one of the four dhams.

India Doing for India

Maybe the notion of the shoppers being pilgrims isn’t so silly though, because beyond the intricate dance of khareedari, beyond the practiced rhythm of negotiation and selection, there is the undeniable quality of the silks themselves—the years of skill, tradition, and patience woven into every shimmering strand.

And at the center of it all stands Anandana, a force of vision and resilience.

It is one thing to run a business competently; it is another to reshape an entire industry, breathing life into a craft that was slipping away. She did not merely seek profit—she sought to revive a tradition, to uphold the romantic ideal of handmade silks, ensuring that the skill of Banaras’ weavers, dyers, and artisans would not fade into obscurity.

Her boldness not only provides livelihoods but helps sustain India’s heritage, and reaffirms its identity.

To me, this is India at last doing for India itself—not waiting for outside intervention, not bending to fleeting trends, but preserving, refining, and elevating what has always been its own greatest strength.

And as I reflect on a decade of learning Hindi, of immersing myself in media and conversations with the people who shape this evolving nation, I see it again and again—this transformation, this reclaiming of identity through history, culture, and craft, this insistence that tradition and modernity need not stand at odds.

At the end, our hands carry more than silk. We carry a piece of India’s living story, stitched together by bold ideas, skilled hands, and the unwavering belief that revival is always possible.

Beyond the Sale: A Gift Woven with Tradition

The reason I was bought a saree and joined the shopping adventure wasn’t for myself, it was for a friend.

Some of the fabric I purchased will soon take shape as big, beautiful cushions for her living room, transforming tradition into something deeply personal.

She was astonished at the quality of the silk, overwhelmed by the delicate aquamarine hues, its borders stitched with pure silver threads, shimmering like quiet waves.

In her hands, this was more than fabric—it was a gift wrapped in heritage, in skill, in centuries of craft.

In which I see a pattern developing…

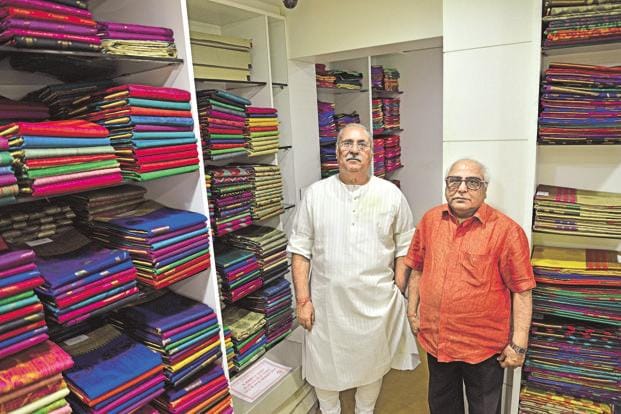

The shift from Stuti Weaves to JDS Banarasi Sarees wasn’t entirely planned, but when you’re already nearby, and when the women in your group have done their research I think it becomes inevitable. They knew JDS was a shop worth visiting, a place representative of Banaras’s textile legacy. I think they wanted something to remember the trip by as well. But here, naturally, the husbands and partners staged their revolt, planting themselves outside with a collective determination to avoid another fabric deep-dive.

I, however, found myself swept in. At first, I was just checking things out, going along until the temple-like ritual hit. An attendant wanted my bags turned in. Shoes removed. A formal induction into the temple of JDS Finest Banarasi textiles. That was it. I made my move to leave.

But no, Intercepted. An entire cluster of women blocked my escape—literally grabbing my elbows and steering me to the private elevator to the showroom on the third floor, their strategy impeccable. “It’ll be an experience,” they promised. And—most damning of all—“We won’t be more than just a couple of minutes.”

That was all it took for a childhood flashback to barrel into me—a near-comatose state induced by my mother’s fabric shopping, where “just a couple of minutes” stretched into what felt like three days. Maybe my youthful mind exaggerated the duration, but the memory remained vivid: aisle after aisle, bolt after bolt, a slow-motion surrender to patterns and textures.

I recovered from my flashback, let out a massive belly laugh, and called them on their obvious lie. “Some things are common in every culture,” I said, “I have been told that same lie countless times by the women in my life, so why should you be any different!” shaking my head. The deception was universal. They just giggled a bit, and my only wingman Ravi gave me a knowing look.

So, I did come along. Maybe this was a chance to find something more for my friend’s cushion project. A justification, however thin, was enough. I am glad I did in retrospect because what followed was a wonderful experience.

Stepping into the showroom at JDS felt like walking into a library of colors, every shelf neatly stacked with clear plastic packages, each one containing the promise of some new visual display—whether in shade, weave, or both.

I was hooked immediately. I had no conceivable use for a saree back home, and I certainly couldn’t pull off wearing one myself—but oh, how I wished I could! I wanted to tear into every package, to feel the weight of the fabric, to witness the shimmer shift beneath my hands.

India’s fashion is 100% not about ready-to-wear. Everything is meant to be tailored, adjusted, perfected to fit each person individually. It felt worlds apart from my middle-class American instincts, where off-the-rack dictated nearly everything.

The shop pulsed with energy, a hive of sales associates and motivated buyers. The women in my group vanished in an instant, each swept off with their respective representatives.

And then, my salesperson stepped forward.

Hesitant in his English: “What are you wanting to see today sir?”

In my broken Hindi, I asked for something the color of hara, um, lauki—bottle gourd green, a shade hovering somewhere between seafoam and turquoise.

His eyebrows rose and his eyes lit up, and he vanished.

Moments later, he returned, triumphant—the exact shade. Perfect.

Encouraged, I requested something in tarbuj ka rang (color of watermelon). He rushed off, swift and assured.

But when he returned, I hesitated. Where was the pink color?

One of the women from our group stepped in, and he explained—the hidden folds revealed sections of fabric meant for different parts of the ensemble. Then, with a flick of his wrist, he unfurled the suit fabric. Another attendant caught the other end, stretching it wide. The watermelon pink shimmered into view, deep within the folds. Different sections, meant for the pantaloon, the blouse—the suit ensemble, unveiled themselves, a wrinkle I hadn’t anticipated. A small, unexpected personal victory though: my Hindi had worked after all.

I smiled, laughed, and the salesperson did the same.

“See sir, very nice color!” he said, delighted.

Without realizing it, the words came naturally: “Mujhe ye JDS ke sareyaan bahut maan pasand hai.”

The phrase slipped, shaped by immersion rather than intention. The salesperson beamed; happy our cooperative effort had worked our way to a sale for him and the perfect piece for me.

I was handed a handwritten slip with the pricing information and directed to the cashier on the second floor, where my purchases would be packaged and presented to me after payment.

Ravi was ready to go as well, so we navigated our way there together.

As we sat waiting, he turned to me with an easy smile. “How’s your Hindi coming along?” he asked, his curiosity genuine. Then, almost sheepishly, he admitted, “I only know only a little Hindi myself—I’m from Hyderabad.”

I grinned. “Then we can mangle this beautiful language together,” I said in Hindi, laughing. “And switch to English when necessary.”

That seemed to break the last bit of formality, and soon, the conversation opened up. I spoke about my experiences so far, the moments that had caught me off guard, the rhythm of India that despite being both chaotic and mesmerizing I was truly enjoying so much, it all felt very natural to me. He asked how I had found India—what I thought of the cities, the crowds, the pulse of it all.

I was honest. I told him it was a country I had fallen in love with, long before I ever stepped foot on its soil, through its music, its films, its culture.

I did my best with a few Hindi phrases here and there, just to keep up the playful momentum, and to my amusement, a man sitting behind a desk chuckled at my efforts. Another account clerk laughed outright, clearly entertained by the linguistic dance Ravi and I were doing, much less than half-fluent on my part and over half-improvised, all good-natured. Soon enough, I was given my invoice, paid my bill, and thanked everyone as I made my way back down to the first floor.

Outside, the air felt lighter, almost celebratory. I stepped past the threshold, still replaying the exchange inside—my halting Hindi, the unfurling saree, the color hunt that had somehow turned into something more. These episodes I experienced on my journey were blinding in the sheer amount of new sights and customs and language and just everything. Every one of these was completely overwhelming and I have had to process these over time after my return. In fact, writing about these episodes has been the thing that has truly unlocked my experiences there!

Then, Ravi appeared, his expression carrying something unspoken. In his hands, a neatly wrapped package—a saree, luminous even through the folds of clear plastic.

“For your wife,” he said, offering it to me with quiet reverence. “And an invitation from JDS himself to please return to India again.”

I blinked, caught off guard. “But—” I started, confused by the generosity.

“You spoke to the owner of JDS himself,” Ravi explained, smiling. “He was deeply touched that you came for the Mahakumbh Mela, that you took the time to learn even a little of the language.”

It hit me in an instant—the unassuming man inside at the account desk, the effortless exchange, the ease with which I had stumbled into something far deeper than I had realized. I had spoken to him simply, naturally, without knowing I was addressing the very person who had built JDS from the ground up. And yet, somehow, it had mattered enough to him to make this very generous gesture. I was speechless. The saree, the invitation—they were more than gestures. They were acknowledgments that by words alone an unspoken bridge was built between us.

Bonded by Threads: India’s Textile Legacy and Global Future

Finished with our shopping for the day, I realized carried more than fabric, I carried the realization that these shops were more than simple storefronts. Both Stuti Weaves and JDS Banaras, in their own way, stood as quiet but resolute declarations of India’s pride—not just in its textiles, but in its independence, its evolving commerce, and its rightful place on the world stage.

Banaras has always been more than a city—it is a statement, a quiet declaration of India’s resilience and evolution. Shops like Stuti Weaves and JDS Banaras embody this dual spirit: rooted in centuries-old textile traditions while navigating the shifting tides of modern commerce. Though the skills involved are ancient, the business end I feel can trace their existence, thriving and unapologetically proud, back to the Swadeshi movement, where Gandhi’s call to weave khadi was both a rejection of colonial dependence and an assertion of India’s self-sufficiency. Today, these shops stand as testaments to that enduring legacy, not just through the sarees they sell, but through the confidence they exude in India’s commercial and cultural strength.

For the artisans within their walls, weaving is more than livelihood—it is preservation, expansion, transformation. It is the careful threading of tradition into the future, the marriage of history and industry. The owners of these businesses do not merely sell fabric; they champion a national identity, proving that commerce and heritage are not opposing forces, but complementary ones. The pride they carry—visible in their storefronts, in their conversations, in the generosity of moments like yours—is infectious. It is the kind of pride that makes visitors feel welcome, that makes them momentarily belong.

These businesses, these threads woven through India’s economic tapestry, are not just surviving in the global market, they are shaping it. They are India’s declaration that its craftsmanship, its trade, its artistry deserve the recognition of a world power. And not simply because they hold history, but because they hold the future, and they hold it with skill, confidence, and a deep, unwavering belief in India itself.

Leave a reply to Hari Cancel reply